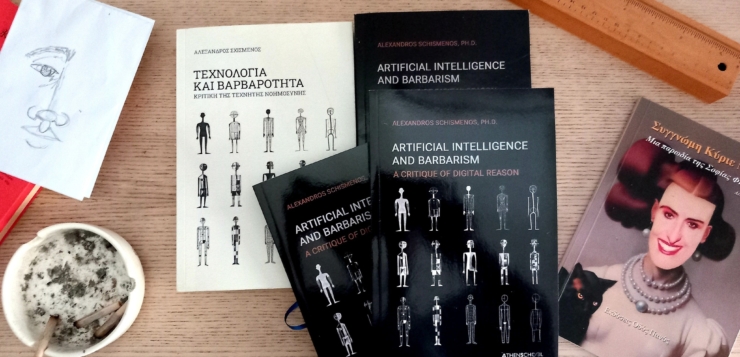

Alexandros Schismenos, the outstanding Greek scholar of philosophy who has written insightfully on Cornelius Castoriadis and Martin Heidegger, continues his inquiry into vibrant themes of social and political significance. There is a search to renew the human prospect by reinvigorating autonomy (popular self-directed organization). And an impending confrontation with the reality of a decline in culture, merit, and civilization-ethics from a working class and democratic point of view.

His latest book on artificial intelligence (or A.I.) suggests a critique of digital reason where not simply unknown advantages and disadvantages are along the road ahead. But there is likely a barbaric fate in front of us. It is crucial to learn with Schismenos why this is so.

Advantages and Disadvantages? Likely A Barbaric Fate Ahead

Whether we see A.I. in ChatGPT, robots (from factory assembly lines to caregivers to intimate partners), algorithms mirroring our likes and desires back to us, self-driving cars, retail customer assistance chatbots, digital assistants (from Siri to Alexa) for navigating roads and playing music, facial recognition for security systems, medical diagnosis, surveillance and fraud detection, virtual travel booking agents, playing games, drones (we are told to deliver pizzas and replace fireworks shows), eye glasses that appear to integrate the internet with your brain, there is cause for uncertainty and for many alarm.

Even for those humans who assimilate this technology quickly, they may be unclear about the terms of human association undermined and social relations left behind. In the last ten years, the imperial military industrial complex has also used A.I. to target assassinate people without trial (all over the world — most recently displayed in ‘Trump’s War on Drugs’ in the Caribbean), and to put fail-safes in the technology to undermine human hesitation.

Instead of Dystopian Assumptions, A Techno-Skepticism

Rapid change, whether little understood by older humans or quickly assimilated by youth, may be destroying the human prospect in multiple fields: the arts, judicial affairs, economics, politics, culture, the ecology. The very terms of intimacy, presence, and community are under attack. Still, Schismenos brilliantly addresses this matter by first acknowledging and defining ‘technoskepticism,’ and then challenges the reader to address the issue with a proper measure of reason, before considering how A.I. will impact humans metaphysically, ideologically, and how we can reclaim possible futures against the current of these disruptive trends.

A.I. Not Shutting Down? Do Humans Turn Off Themselves?

Schismenos’s introduction grabs our attention right away beginning with a quotation from Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) that reminds that ‘any thing’ that is self-sufficient and autonomous will wish to preserve itself. He contrasts this with the recent news (2025) that certain forms of A.I. are not following the explicit directions of its programmers that it should allow itself to shut down or turn off. Schismenos inquires: ‘How long have we really been using A.I.?’ Put another way, how many decades are humans behind in their social, ecological and community control of science and technology?

Then he suggests that while A.I. has always been the basis of science fiction dystopian narratives, we are not really living in a technological revolution today. The technological foundations of what is termed A.I. came with the Age of the Internet in 1991, and the global and commercial use of it has been around for 30 years. In 2001 the algorithm for Data Extraction was invented along with Graphic Game Data Processors (GGDP) and Large Language Models (LLMs). In other words the disassembling, classifying, and reassembling data according to provided patterns has been going on for more than 20 years. A new push in data came from the Covid crisis in 2021, where many stuck at home abruptly shifted the focus of human social functions and tasks.

Problems with Automation and Artificial Intelligence: Are Humans Not to Socially Produce and Reproduce Anything but Only to Consume Things (Even Ideas and Images) in an Unfiltered Manner?

And yet the concern about a decline in human culture (a poverty of experience) in relation to industrial organization was raised by Walter Benjamin back in 1933. Benjamin, as Schismenos explains, seemed to suggest that a proliferation of ideas meant a constant renewal of good and bad, insightful and discredited ideas. That it was possible to consume what interested us, unfiltered into a type of gluttony that undermined the need for, and discarded the protections of, human association. If human and social association ethically filters what we consume and think, A.I. starts to repeat back to us what we desire or wish to spectate as private individuals with no cooperative assessment or judgment.

Barbarism of Target Assassination by Drones without Trial vs. Popular and Self-Directed Judicial & Military Affairs Yet to Emerge

If we keep in mind target assassination from the sky (with some combination of drones and A.I.) as a new constant, then people are being killed with no discussion of going to war, the terms of judicial and military affairs, or foreign relations. Schismenos inquires: is this relatively new? No more than the last ten-twenty years? Actually, we increasingly find drone attacks on civilians endorsed by, and in collaboration with privatized mercenary forces, with what are said to be post-colonial, peripheral, and underdeveloped Global South governments in Africa and the Caribbean.

Schismenos explains when we look at the intersection of the philosophical ideas of Schiller, Voltaire, and Hobbes, that brought an apparent consensus on Enlightenment reason and human rights, even then these thinkers understood humans remained barbarians. Why hasn’t deception and savagery been undermined?

Human Rights as an Aesthetic Dimension of Racism and Imperialism

In short, if philosophical ideas were popularized, they did not improve human practice exactly because they were not equally pursued and achieved by everyone. If they are consumed (or not) by everyone they are not created and established by everyone.

And so reason and human rights, arguably in Napoleon’s time (1769–1821), became an aesthetic dimension of racism and imperialism. Hierarchical powers could conquer under the false flag of reason (reason participates in barbarism as much as religion does), liberty, and beauty. Certainly a republic was openly a minority rule government of professionals and specialists. If the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) established the first black republic, what did the modern epoch of civil rights and colonial freedom (1947–1993) establish? The same propertied individualism and management of servile lives was called ‘equality.’

Citizenship and constitutions can become absolute ideas without questioning them. But more importantly because most did not take part in founding, framing, and constituting a society of their own. And taking part in an insurgent social motion for a time doesn’t mean we really decide the values we wish to place on ourselves. Further having constant discussions about what it is to govern ourselves without organizing impending confrontations with impediments to self-directed humanity is also a problem.

And so the state (in the name of administrative rationality) was able to divide ‘civil society’ and ‘culture’ (passive obedient spaces — some are bovine enough to call these safe spaces) from those who made vital decisions including coercion and shaping life at others expense. In short ‘freedom,’ Schismenos explains, was invented as a passive principle hundreds of years before the Age of the Internet and A.I.

If so, why wouldn’t we passively consume others’ ideas and images as private individuals and not call this a type of liberty? Further, why wouldn’t we not increasingly consume our own desires and thoughts mirrored back to us (the algorithm) without regard for having to come to terms, analyze, and understand those who don’t think like us? Further, what does it mean when we passively consume everyone else’s barbarism for entertainment?

Technology & Machines Cannot Embody Intelligence

At this contemporary moment humans are responding to A.I. with two conflicting sensibilities, technophilia and technophobia. But Schismenos suggests an intermediate stance beyond uncritical love and excessive fears be opened up: technoskepticism. The author’s critical stance starts from the premise that we must clarify that technology (or machines) cannot embody intelligence. Rather, intelligence is part of human nature.

Our human nature is not neutral but it is the primary condition of any judgment (that is an ethical evaluation, but also the aspiration to found social relations that might be termed good or beautiful). Schismenos’s Castoriadis calls this the enactment of technique. In other words, humans create and make things, and speak things (social relations) into being.

Human Nature: Not Neutral or Inherently Ethical but the Primary Condition of Judgment

Already we see that A.I. cannot be intelligent in the self-directed sense, but only follows a self-interested (most often programmed by others) pattern. Humans can decide what we will produce, when we will produce, how we will produce. We can decide to produce love, commerce, or killing — and we can decide to stop and refuse to be programmed by others.

But let us say we wish to negotiate and search for power within the dominant socialization and think we can pursue human culture at the same time. Schismenos seems to place forward a challenge: Can humans be self-interested and self-directed in the autonomous (self-organization) sense? This has everything to do with whether the technologies we use will produce self-directed creative, democratic, and human outcomes. Or can being self-interested amount to agreeing to allow education and ethics to mean no substantial democratic (majority rule) engagement, and allow technology (which is not value neutral) to make the most profound decisions that impact the human prospect without us noticing?

How Can Words Cover Up Issues of Justice, Love, and Caring?

In 2024, a Japanese novelist wrote 5% of a fictional narrative with ChatGPT. What did she use it for? Her theme was how loving, caring, and vague words could cover up issues of justice and killing. And through the internet she found, through what Schismenos calls the graveyard of writers, all the words she needed.

But why is it that many find ChatGPT useful (and others find it a mystery) for crafting their resumes for employment? Perhaps, because employer’s algorithms define a set of action or activity words that they wish to ‘hear’ or ‘see’ that very often doesn’t correspond to a literate person with a vibrant vocabulary expressing themselves with nuance and independence. Instead, as with SEO (Search Engine Optimization) in journalism and advertising, we are told to repeat even plagiarize key words so our writing, that purposely says nothing original and insightful or even gets ordinary people’s attention in an unorthodox manner, rises to the top of search engines.

Language is A Game: It Can Be Programmed So Genuine Humans Are Not Involved or Can’t Take Part Without Degrading Themselves

Schismenos following Wittgenstein, reminds that language for most is a game. And if A.I. linguistic models only need four elements: the source, the receiver, the transmitter, the channel — say to gather resumes for employment — than it doesn’t need humans with the faculty of reason, emotion, or a sense of merit, the good, or beautiful. And the process can pretend to be objective because humans are apparently not involved.

Improvising with Aristotle, Schismenos says the process of communication through A.I. is soulless and inanimate. But it can imitate the ‘artifact’ of subjectivity — it can mimic feelings, emotions, and tastes. It can ask how was your day? And reply that they regret you are having a bad day. It is either programmed to or mirrors the dead objects or feelings of the past. Like an archaeologist that inquires in the past, when you engage A.I. it communicates with you, accepting that like an ancient cracked pot, as a human we used to have social significance. And if you curse out Siri with an f-bomb, it replies that is not very nice or considerate. But what is really inconsiderate is, while we are laughing at this apparent toy, how A.I. blocks out and minimizes the flow of independent thinking.

Schismenos makes it clear machines cannot have a conscience. But he asks us to consider do we know what it means to be conscious beyond human consciousness? A conscious human implies a person has character and can be supervised or judged. This may not be so attractive if we think in terms of hierarchical bosses and servile lives below. But relations of love and mutual aid are also evaluated and coordinated. What ethical association is not subject to challenge, criticism, or possible improvement?

The Human Brain is Not Consistently Conscious (Even Without A.I.)

The author takes note of recently published long-range (but inconclusive) research about two scientific theories of human consciousness that speak to the aspirations of A.I.

First, the brain is not consistently conscious when different parts share and analyze information. Second, the brain is not consistently conscious where labelling and projecting information to transmit it.

This appears to mean that A.I. cannot develop an ethical judgment through sorting and classifying information (labelling it good or preferred) or a reliable self-awareness knowing that after they share information their counter-part will desire accountability. A.I. may be subject to correction by a programmer but cannot learn to respond to every possible human concern. This is a result that it transfers an artificial human environment as the basis of the information gathering or exchange.

Where LLMs (Large Language Models) have gathered many apparently quality science journal articles, for example, it overstates its claims or makes generalizations, exactly because human authors do. But can LLMs be created that are specialized to assist everyday people in pursuing direct self-government in economic planning, judicial affairs, foreign relations, education, ecology, and cultural matters? What if an LLM was created that foregrounded the archives of every left communist, libertarian socialist, social ecologist, anarchist and every thinker concerned with a project of autonomy? Would this be an improvement upon a google search or ChatGPT search that sifted through all of this information on the internet already but has no means of going beyond muddling randomly thought?

If We See the Barbaric Potential in A.I., We Reject the Fight for Hegemony

Two dilemmas in such a project include the following. If we isolated all of this supposed largely qualitative material, it would still have limitations and blind spots. People would still have to think for themselves and improve on such archives. Further, humans need to study closely ideas they apparently abhor (not just which they approve) to discover the structures, creative conflicts and dynamic tensions of how these work — not simply the critiques of them. Would we study anarchism and communism as assessed only by capitalists, imperialists, and fascists? Then why study the latter only from the perspective of the former?

In both instances, humans (with and without A.I.) can replicate the emaciated skeletal frameworks of ideas in communication they don’t really grasp in full or even substantially in part. After all, even radical autonomous ideas, especially if we did not create them ourselves, need scrutiny. Not for sophistry or reinvention of the wheel. But to make sure we are not simply along for the ride.

Many assert an identity as self-directed, as autodidacts often do, while relying on a plethora of sources to mediate knowledge in fact. A.I. creates an illusion: multi-directional flows of teaching and learning are not necessary. Just as communists who absurdly fight for hegemony, we must be careful not to wish for an anarchist algorithm. Hegemony is not simply an opaque word that suggests the masses are deaf, dumb, and blind under false socialization and miseducation. But those who ‘fight for hegemony’, strive for their preferred passive socialization of the masses (they know will not be fully or substantially understood) as an aspirational top-down process of liberation.

Plagiarism Software: A.I. Doesn’t Create Anything

If A.I. doesn’t create anything, and we recognize it as nothing more than plagiarism software, we have a larger challenge than the covering up of the global decline of basic literacy, which all educational institutions, public and private, high and low, have been covering up for some time. What Schismenos calls the ‘black box’ problem, is when using A.I. for research or asking questions, we don’t know why the specific sources are chosen to inform us, in contrast to other users of the internet.

Schismenos argues the risk of plagiarism is real but it is the smallest risk among many. He pushes further. Why can’t everything on the internet just be the common property of all? It cannot for the net and its features are private and marketable products. And while copyright laws have yet to catch up with all the implications of the technology, it is difficult to say when an essay, poem, or song found on the internet can be asserted as in the social and political control of anyone.

Schismenos suggests when we consider some attempts at making international law to govern the internet, this effort is broken down into categories related to levels of prohibition, privacy, and risk. Concerns with pornography, racial and ethnic discrimination, but also what is defined as false news. As our philosopher looks further into proposed laws, these document ‘the game behind the game.’

First, A.I. manipulates group behavior and distorts decision making. Second, A.I. exploits the socially vulnerable. Third, A.I. uses biometric categorizing systems gathering data on race and ethnicity, trade union membership, philosophical and religious views, sex life. A portrait is made of each user. This is proposed as illegal unless if users are advised such information is being gathered (usually for immediate business purposes) or sale to others, or law enforcement is gathering the data.

Fourth, A.I. creates behavioral portraits of internet users leading to detrimental or disproportionate treatment in unrelated contexts. For example, criminal profiles are made of users. But also notes are taken how someone might be manipulated face to face by authorities or those with this information. Fifth, A.I. functions as data for a real-time crime center, where internet or smart phone users can be pursued physically when identified as missing persons or carrying out serious crimes. Sixth, A.I. expands facial recognition from internet scrapings or close circuit tv or camera footage. Seventh, A.I. takes note of emotional patterns in workplaces and schools.

While China’s one party state has used many of these techniques to surveil their large population, we also see for apparent entertainment and education the practice of ‘deep fakes’ where we see historical figures or contemporary celebrities voices’ appropriated to display them with great authenticity saying controversial and vicious things. We have started to see on the internet speeches by long dead political radicals and martyrs. Only serious scholars might notice that people from decades ago are peculiarly wielding contemporary language that was not in use decades ago. But the average person cannot tell.

What does this mean for future judicial affairs where evidence is produced of humans in their own voice saying things they didn’t really say? Schismenos underlines that despite much talk of ‘ethics’, the A.I. applications are designed and sold based on their capacity to advance profits and extend control over its audience.

Surveillance Capitalism

Schismenos introduces us to a new economic order. A.I. used the human experience as free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction and sales. In other words, when using the internet, we are constantly shown goods and services that follow our behavioral pattern. For example, if you buy or look at a lot of books, electronics, or dresses, these are perennially placed in front of your nose. But far more than just advertising for things you might consider purchasing, is your data is bought and sold, by private and state security that takes what many call their human rights away. This might be seen as digital dispossession.

Where this technology is applied to what used to be basic accounting under the state and capital, A.I. can start turning off our access to water or electricity. Partially as a result of the limits of the feedback loop. A feedback loop, a cyclic process of action, monitoring and analysis, may allow a thermostat to self-regulate. Surely it will be colder in the winter, and we may wish a higher temperature to make us comfortable. This can be automated. Following the same A.I. process, what if you can’t pay the water or electric bill, and systems (beyond immediate human oversight) expect payment by certain deadlines? Dispossession can become automated.

Regulation or the Game Behind the Game

Schismenos shows us that different approaches to regulation of A.I. by government, some wish no regulation at least for the next ten years, raises another matter. How does the public (in contrast to specialists) discover “the game behind the game,” without at least some accessible discussion of the terms of regulation?

Our philosopher inquires how do we separate horizontal and direct democratic human relations from the A.I. cultures proliferating now? Can we pursue a society based on mutual aid based on free and open circulation of knowledge and information informed by different social and economic values? He explains the human world is not an inherently functional or rational system.

Our Lives are Shaped By What We Know and What We Do

Our lives are shaped by what we know and do, that is the terms of community, behavior, and values we institute. This is not the same as being conditioned or socialized to function within institutions created and directed by others.

Schismenos warns against billionaire technocrats who have purchased governments, and wish to quantify people to subordinate them to capitalist profits and accumulation. The digital automation of politics and the desire for complete control of social events, while the technology seems to be disinterested and without virtue, and serves the agenda of private capital, the ideas being wielded are not new. Conspiratorial propaganda, far right movements, support of select state oligarchies (regimes based on rule by the few), the attempt to interfere in national and international elections have a historical pattern before these technologies.

Dystopian Technocracy Abolishes Self-Directed Political Values and Forms

Schismenos argues that this dystopian technocracy relies on certain politics while seeking to abolish other political values and forms. Their dependence on politics, human struggles for power but also desires to arrange society as they wish, is the vulnerability of Big Brother.

Only human dependence can legitimize nation-states, republics, and other terms for elite representative government. While normatively living by a veneer of civil or human rights, A.I. applications and systems are taking these away. It is difficult to say that raising awareness is the solution. What is required, says our philosopher, is a transformation of how we see community. Confronting and dismantling digital barbarism can only happen if everyday people believe they can imagine, found, and form their own terms of direct self government. This is not a result that humans will ever be beyond prejudices, blind spots, and mistakes.

Distinguishing Human Prejudices and Blind Spots from Self-Limitation

Our philosopher asks us to consider that we mistakenly accept our identities as isolated digital persons who communicate in fragments, and through social media we create networks for isolated projects where the system suggests ‘friends’ to us as it surveils us.

Schismenos seems to suggest there is no mode or application on the internet that allows us to make all decisions about our lives. The existential problem we face is our cultural and social behavior is being separated from our capacity for self-directed political and organizational behavior.

One reason we need global friends and coordinated struggles is so we can teach each other local knowledge about freedom movements that others cannot have in other parts of the world (at least without sharing). It is difficult to grasp, (beyond what is termed by Schismenos ‘telepresence’, the feeling of being present while situated remotely), the quality of assemblies and demonstrations we should be taking part. Are we living through an epoch where solidarity is organized among comrades and co-workers who never meet each other face to face and who don’t even regularly speak to one another? How can this be reliable or sustainable?

While some local knowledge and experience of politics can be verified by extensive internet research, for example who funds ‘activism’, A.I. can discourage reading carefully even one of the articles it selects to justify its offerings. The fact remains that ‘progressive’ mass mobilizations, when not self-directed and insurgent, are usually products of the mailing lists and social media of the affiliates of the left block of capital, its political parties, and cultural apparatus. Trade union hierarchy and non-profit foundations (decrying privilege and funded by billionaires otherwise denounced) are often the origins of what even experienced observers are quick to mistakenly declare autonomous movements.

Self-Directed not Automated Freedom Movements

Separate from real confrontations after midnight where broken glass is everywhere and the whiff of teargas is breathed in, these “activists” often set and reset the slogans of freedom movements to contain radical democratic instincts, and rely on more conservative forces smearing mediocre personalities and ideas to indirectly legitimate them in mass media.

As with the many forms of A.I., we cannot assume that our freedom movements are not automated and artificially designed against our will. Telepresence doesn’t inherently control our minds. But it ensures we are not really present. Mass mobilizations and protest rallies, marching shoulder to shoulder, can also be robotic processes with minimal human input.

Reproducing False Knowledge Systems or Renewing Autonomy?

“Freedom”, “Justice”, “Peace”, in popular usage were long ago adjusted to states, rulers, and empires. “Democracy” (majority rule) normatively means, in this bizarro world, minority rule through periodic capitalist electoral politics. In the post-civil rights, post-colonial era we accept that “equality” means equal opportunity to enter the rules of hierarchy, diversity in propertied individualism, and inclusion in management of subordinate lives. Most often A.I. will only reproduce and normalize these false knowledge systems as humans overwhelmingly with bad faith and malice invented them.

The danger of a techno-dystopia is not so much that machines develop a personality and refuse to turn themselves off. Instead, they may display a sense of imperial expansion mirroring the humans (not the only current of human nature) that programmed and designed them.

Real Danger of Techno-Dystopia: What We Want and What We Believe

Most humans face the danger of a barbarism, a techno-dystopia, as a result that too many have, for all practical purposes, turned ourselves off long ago. That a significant section of the populace believes education and thinking is only worthwhile if it brings them money, personal power, or prestige under the existing system of domination of the multitudes.

We may only be able to reliably ask of artificial intelligence what we already want and believe. If we are so autonomous, beautiful, and self-directed, why ask A.I. at all? Why not delink from being led around by our own instincts toward consumption and extracting wealth from others?

Delink from Being Led Around By Our Worst Instincts

Instincts are fascinating and worth cultivating when they are half-hidden vital energies and repressed strivings we wish to unleash to make new leaps toward qualitative freedom. But when they are imperial, nasty, selfish, and slothful impulses, society and its technologies should not be empowering these, especially through automating conquering, surveillance, and dispossession. A.I. as a purported technological revolution may be producing only the stylized look of submission.

If we aspire to be independent and ethical (if we wish to preserve ourselves as the human race), with Artificial Intelligence & Barbarism as a valuable accompaniment on the journey, we may discover the savagery and sadistic brutality of digital reason. The key is to remember that A.I. doesn’t invent anything. With a proper sense of self-limitation (knowing we, as individuals and organizations, cannot know everything, oversee everybody, and complete humanity — not simply for technological but ethical reasons), we can minimize our instinct to consume information and things (and transform humans into things). We can renew our sense of initiative to make real friends, be present in each others’ lives, and create refreshing terms of being and ways of knowing, and reproduce social relations that renew (and limit) the human prospect.