by Alexandros Schismenos

Introduction

As we move deeper into an era of algorithmic governance, technoskepticism has evolved from a niche critique into a vital survival strategy. Despite the noticeable limitations of current AI technology, from hallucinations to ecological destitution, modern societies have irreversibly crossed the threshold of the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution [Industry 4.0], which is the current phase of the digital ontological revolution that began in the last years of the 20th century and is rooted in Tim Berners-Lee’s idea of the Semantic Web. However, digital technology is moving away from this initial sociocentric idea, toward AI integration and automatic administration.

Since 2016, the global pandemic of 2020 and the subsequent shutdowns have accelerated the digital envelopment of capitalist societies worldwide, with major sectors of governance, social services, and market transactions moving to the digital sphere. For a brief period, social interactions and social communications became solely digital telecommunication, and even after the shutdowns, a significant portion of human interaction became digital in a more permanent manner.

In late 2022, just over a year after the pandemic, the launch of OpenAI’s ChatGPT introduced LLMs to the broader global public, leaving most stupefied. Since then, AI technology has taken hold of social imagination, fermenting both dreams and nightmares.

In February 2025, the DISCO Network released their book “Technoskepticism, Between Possibility and Refusal” as a survival strategy for marginalized groups against systemic inequity.

In the framework of the DISCO Network, every piece of software carries the baggage of its creators’ biases—a reality that necessitates a strategy of ‘informed refusal.’ This mirrors my own concern regarding Digital Reason: the way algorithmic logic colonizes our public time, transforming shared social experience into a series of quantifiable, extracted data points.

In my recent book, Artificial Intelligence and Barbarism: A Critique of Digital Reason (Athens School 2025, Athens), I propose we search for a middle road, based on public reflection and informed criticism, that I also called Technoskepticism.

The consensus is clear: we must be skeptical of Artificial Intelligence and see technology as inherently linked to power. We must recognize that technology is never a neutral container.

However, I call for a more political and ontological conception of democratic technoskepticism. To properly explain what I mean, I should first define technoskepticism against the opposing extreme positions of technophilia and technophobia.

Technophilia against technophobia.

Dreams of human liberation from menial labor via technology have tormented the social imagination at least since the time of Aristotle, who asserted that mechanical statues could replace slave labor if they would follow commands [Politics 1253b53]. However, in modernity, they became inexorably entangled with the ambition of rational domination over nature, formally expressed by Descartes in 1635, when he aspired to total knowledge that would “thus render ourselves the lords and possessors of nature.” [Descartes 1909]

Castoriadis observed that Descartes is not merely expressing a personal desire for the total understanding of nature, but rather gives literary form to the emergence of a novel social-historical representation of being, “whereby all that is ‘rational’ (and, in particular, mathematizable), that which is to be known, is exhaustible de jure, and the end of knowledge is the mastery and the possession of nature” [1987: 272]

The imaginary impetus behind the development of AI technology is the spearhead of capitalism’s drive toward the imaginary goal of total mastery of nature, both inanimate and human, by means of digitization.

Expectations around AI are developing way faster than the actual technology, but along with expectations, investments also increase, and AI companies in recent years are the most highly financed businesses worldwide.

This is the main reason why AI expansion is increasing, because it is driven by an explicitly political desire of techno-capitalist elites that are eager to cash in on AI’s capacities in surveillance, classification, personalization, manipulation, and monitoring of the global consumer populations privately.

This political force, personified by the President of the U.S.A. D.J. Trump and his government has helped AI companies overcome social and political obstructions and more or less obscure the public awareness of AI’s deep and irreversible impact on both the natural and societal environment. Governments and state authorities worldwide promote and enforce the official structural version of what I would call technophilia, the idea that technology will bring forth utopian, however one imagines it. We could say it is a form of instituted technophilia from above, expressing the ambitions and interests of the upper echelon of social hierarchy.

One the opposite side stands the growing trend of technophobia, spreading across pop culture, social media and public imagination, that is deeply rooted in the nightmarish social cost of the Industrial Revolution and the fear of enslavement by the machines that combines the social-historical experience of the working classes and colonized people with hellish representations of a dystopian enslaved humanity across popular arts, cinema, literature and mass media. Perhaps the most famous iteration of technophobia regarding AI came from Dr. Stephen Hawking, who said:

“Once humans develop artificial intelligence that would take off on its own and redesign itself at an ever increasing rate, humans who are limited by slow biological evolution couldn’t compete and would be superseded.”

Technophobia is not restricted to the lower classes of society but is widespread across the social spectrum, without any authoritarian political or economic center behind its spread. It is more of an expected social reaction, given the gap between the technical knowledge and future objectives of the techno-scientific apparatus and the public’s fragmentary opinions around technology. But when this sentiment comes also from people who belong more or less, to that same techno-scientific environment, like dr. Hawking, one cannot simply dismiss it like a popular misconception.

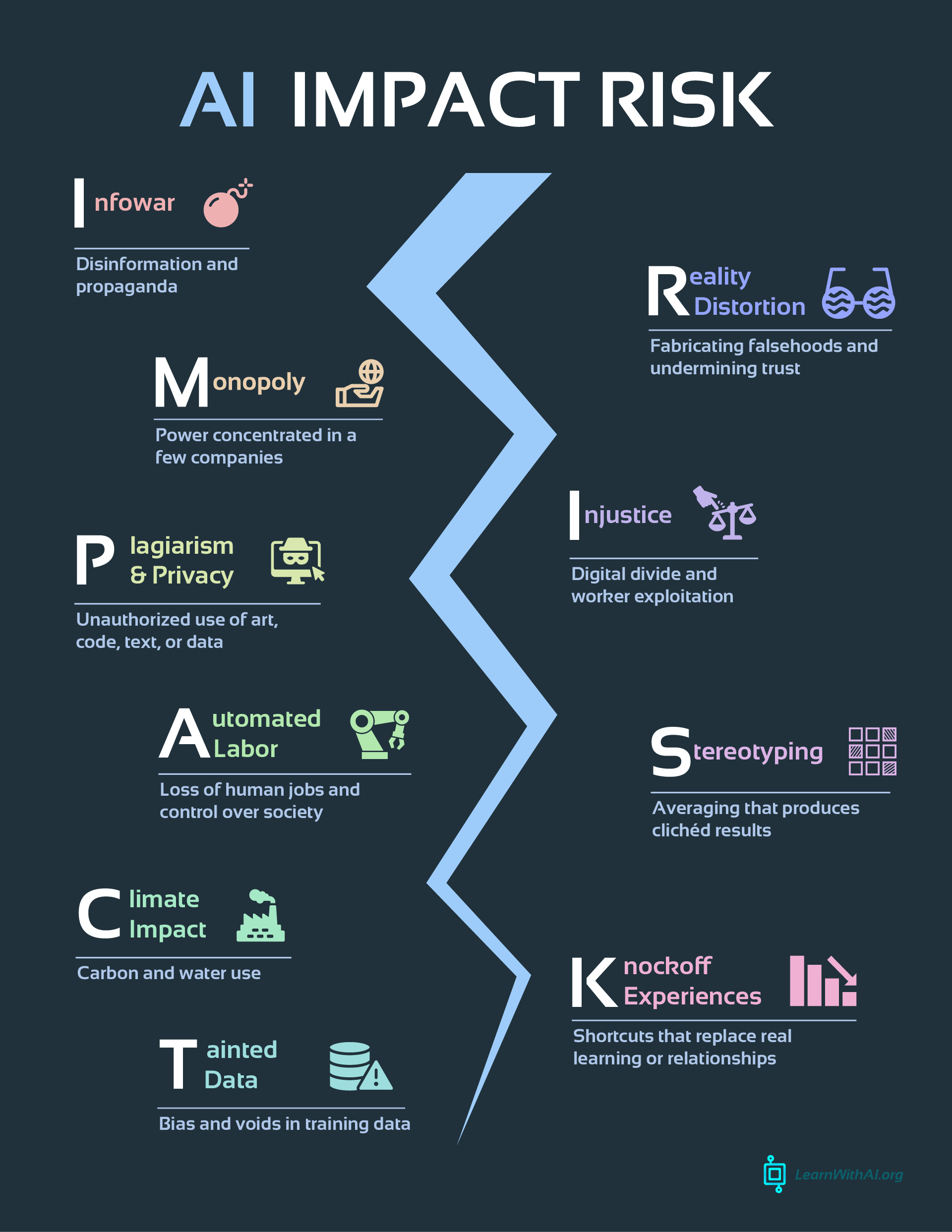

From Gaza to the USA, AI applications have been used by state authorities, private companies, and unknown actors to monitor, classify, target, influence and manipulate populations, voters and individuals, in a way that directly compromises public discourse and dilutes common knowledge by the spread of mythinformation, deep-fakes, and AI-generated images of a distorted view of reality.

Image has been used for propaganda of the dominant imaginary significations since the dawn of society, given that dominant imaginary significations are formulated into social representations and that meaning is always represented symbolically.

But with the advent of LLMs, we have automatic generators of highly realistic images in an instant, and we also have the means, the Internet, for their unchecked proliferation on a global scale. In such a time, technophobia seems reasonable. However, it is a trend based on sentiment, not logical thinking. There is no turning back to the pre-digital world, albeit by a worldwide catastrophe, which no one would desire. We should be cautious of technophobia for its inherent reason, taking note of the fact that it can lead to the path of irrationality and the complete dismissal of scientific research and rational critique.

Moreover, we should be able to discern that behind their explicit opposition, both trends share an implicit imaginary schema: the conception of technological progress as an extra-historical force that moves the world towards an inescapable future of machine dominance, rising above current political fissures. From this stems the principle of the subordination of politics to technology, which has been given expression in the ideology of technocracy, that is already a century old.

Professor P. Noutsos informs us that the terms “technocracy” and “technocrats” first appeared “in the United States during the interwar period, when liberalism was being challenged by both the conservative political forces of defeated Germany and the revolutionary centers of the “Communist International.”[…] “technocrats” were put forward as experts in accelerating technological development and the “rational” management of its fruits. In fact, the position of “technocracy” was strengthened by the economic crisis of 1929, which triggered the “New Deal” policy and legitimized increasing state interventionism in the unfolding of the functions of industrial capital.” [Noutsos, 1988]

AI enterprises and prominent far-right figures of the “Tech-Bros” oligopolies of Silicon Valley, like Peter Thiel and Elon Musk are the latest version of the technocratic ideology that advocates the transfer of political decision making to technical administration in the form of digital technocracy and technological accelerationism or, what has been called, in a rather pompous manner, technofeudalism, a modern economic system where big technology companies have power similar to feudal lords in the past. [Varoufakis 2024]

At this point, we can regard technocracy as both the imaginary final stage of instituted technophilia and the ideology of digital barbarism.

The philosophy of technoskepticism.

In my opinion, technoskepticism is a philosophical approach to digital technologies like Artificial Intelligence, based on social-historical criticism rather than blind acceptance or fearful rejection. It’s not anti-tech, but rather tech-aware. Technoskepticism is based on the notion that digital technology is a product of the dominant social imaginary of instrumental rationality that envelops our social-historical environment [Floridi 2023] by transforming it into a semi-digital sphere of telepresence. AI as a digital system has no interiority, hence neither intentionality. In terms of Digital Humanism, at the beginning and end of the system are human subjects and intentions with social significance performing institutional acts by means of technology.

In the beginning of the year, February 2025, the DISCO Network of researchers based in the U.S.A. released their book “Technoskepticism, Between Possibility and Refusal” (Stanford University Press 2025), where they advocate for a “survival strategy for marginalized groups navigating the space between “possibility” (using tech for care) and “refusal” (rejecting extractive systems).” They focus on systemic inequity and the lived experience of marginalized groups in the United States, shedding light on the use of technology to reinforce racist and colonial power structures. Their interpretation of technoskepticism is regional, topical, and aspires to empower communities to reclaim technology for their own interest, to bring forth “Justice within the Glitch”.

Nevertheless, besides sharing a common ground, there are differences in reference and scope between the DISCO Network’s interpretation of technoskepticism and my own. The DISCO Network’s version of technoskepticism is more specific to identity and lived experience in the US context (race, disability, gender) and is primarily about survival and care in the face of an unjust system. Their critique is primarily sociological and ethical, focusing on very important but regional issues like algorithmic bias, data extraction from vulnerable bodies, and surveillance, while posing the key question: How does technology disproportionately affect marginalized and historically oppressed communities?

My own approach to technoskepticism is more ontological and political, rooted in the political philosophy of autonomy. I try to address the question: What does AI do to the core human capacity for self-determination and creating meaning (Autonomy)?

I focus on phenomena of the social imaginary like the replacement of political reason with technical calculation, that give rise to new forms of heteronomy (rule by external, non-human source) and the fear of social collapse into Digital Barbarism.

Digital Barbarism is the ultimate loss of Autonomy—our capacity as human beings to create our own laws, our own values, and our own collective meaning. AI, or “Digital Reasoning,” reduces the messy, complex, and unpredictable realm of human affairs (ethics, politics, culture) into calculable, deterministic variables. When collective decisions are delegated to the algorithm, citizens become subjects of Heteronomy—they are ruled by a non-human logic that they did not create and cannot contest.

The DISCO Network’s critique is crucial for understanding who the current AI system harms, but it often stops short of asking what the system itself is doing to our political humanity. This is the question at the heart of the European philosophical tradition. In my view, the meaning of technoskepticism is reclaiming the logos and the polis, subjecting technology to direct, public, democratic control.

This is decisive, given the ethical problems that AI technology raises. While we must continue to argue for an ethical framework in AI design and implementation and support global efforts to press governments into legislating a common set of rules and regulations across AI research and production, we should always keep in mind that the social-historical conditions are not favorable. Technology is dependent on authority and by definition authority prioritizes means of domination over common well-being. Ethics is dependent on politics on a deeper, institutional level and the balance of power shifts towards unregulated AI in terms of financial and political capital and given the ignorance of the broader public on issues of tech regulations.

During the last year, we have stood witness to political authority overcoming legislative barriers in favor of AI enterprises, but also directly attacking institutions of critical research and established ethical committees while using AI tools to influence public opinion and project imaginary power.

We should acknowledge that AI does not care about Ethics, because it is dependent on political authority that can easily shift any ethical responsibility evading legal repercussions.

We should acknowledge that AI does not care about ethics, because nothing ethical is intrinsic to digital technology. This is the reason why we should ponder on the political framework and the possible limitations that should be set to digital authority by civil society and grassroots social movements. This is why we need a political, democratic view of technoskepticism.

We could describe the core principles of Democratic Technoskepticism as follows:

- Technology is not neutral: Technology reinforces power structures by embedding existing social, economic, and political hierarchies into its design, deployment and control. It’s not just about who builds the tech—it’s about who benefits from it, who governs it, and whose values shape it.

- This lead to the need for critical engagement with the issues of technology: Instead of trusting tech because it’s new or rejecting it because it’s disruptive, we may ask deeper questions: Who benefits from this application? What values does it embed? What is the overall cost for its implementation on a social, ethical and environmental level?

- Artificial “Intelligence” is not Intelligence: We recognize intelligence as a natural property that defines subjectivity, intentionality and rationality. However, subjectivity is a quality of the living being-for-itself.

- A digital mechanism is, by definition, not a naturally self-creating individual but a modular inanimate object, a being-in-itself, with no subjective interiority. Current AI models based on LLM architecture are statistical pattern recognition machines. But even the alternative, world AI and neuro-symbolic AI architecture, suggested by Prof. Gary Marcus, would produce logistical algorithmic reasoning machines–in neither case a sentient self-referential conscious being.

- Technoskepticism pushes back against the idea that efficiency, optimization, or scalability should be the ultimate goals of technology. It advocates for human-centered values, creativity, autonomy, and democratic public control of technology.

- On this ground, Technoskepticism is based on Digital Humanism and the resistance to Digital Barbarism. Technoskepticism sees blind surrender to technological systems—especially those governed by opaque corporate and political interests—as the form of modern barbarism.

The solution must be political; therefore, fixing the symptom (bias, data extraction) is insufficient. We must confront the fundamental political form of the technology. Democratic Technoskepticism is the necessary intermediate path:

– It rejects the Technophilic idea that technological progress is inherently good.

– It rejects the Technophobic idea that we must abandon all machines.

– It demands that every significant technological choice must be wrestled away from technical experts and corporate interests and subjected to direct democratic deliberation by the citizenry. Technology must serve the polis, not the profit motive.

The horizon of democratic autonomy that spreads from care and justice to political liberation is what makes technoskepticism a powerful new direction for the debate. But we must always keep in mind that technoskepticism is complementary to the political project of social autonomy, which requires actual political participation in the actual public time and space in terms of direct democracy, commoning, and social ecology. We should not forget that democracy is not just information.

In conclusion

In my view, democratic digital humanism requires a fundamental shift in both our conceptual understanding of technology and our political structures, challenging the prevailing techno-industrial complex.

The key steps in a possible roadmap would involve:

- Overthrowing the Regime of Mythinformation: The first political priority is to challenge and dismantle the corporate and political propaganda (mythinformation) that fosters “technophilia” and presents AI as a neutral, all-solving force. This requires critical examination of AI’s metaphysical claims to “intelligence” or consciousness.

- Asserting Human Subjectivity and Agency: The roadmap underscores the indispensable role of the human subject—as creator, user, and signifier—at every stage of a digital system’s function. This means recognizing that natural intelligence is a uniquely human capacity that cannot be reduced to technical functions.

- Achieving Social and Individual Autonomy: The ultimate goal is to move from heteronomy (being governed by external rules or technological systems) to autonomy (self-governance). This involves people collectively creating the institutions and rules that govern their own lives, including the role of technology within society.

- Implementing Direct Democratic Control: The core of the political roadmap is a commitment to direct democracy. The ultimate question is political: “Who controls the providers of AI?”. This control must be vested in the people through participatory, grassroots democratic processes, rather than leaving it to corporations or centralized state bureaucracies.

- Integrating Theory with Praxis: The philosophical framework is designed to be an active guide for real-world application, linking philosophical inquiry with social movements and struggles for emancipation. The aim is to empower informed decision-making and contribute to a more democratic digital future.

Democratic technoskepticism offers a vision where technological development is not an end in itself but a means to foster an autonomous society based on humanistic values, critical thought, and democratic self-governance.

References:

Castoriadis, C. (1987). The Imaginary Institution of Society, transl. K. Blamey, Polity Press 1987, New York.

Descartes, R. (1909). Discourse on the method of rightly conducting the reason and seeking the truth in the sciences, edited by Charles W. Eliot. Published by P.F. Collier & Son, New York.

Floridi, L. (2023). The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence: Principles, Challenges, and Opportunities. Oxford University Press.

Marcus, G. (2019). Rebooting AI, Pantheon Press, New York.

Noutsos, P. (1992). Η Σοσιαλιστικη Σκέψη στην Ελλάδα, τ. Γ’, Gnosi ed., Athens.

Schismenos, A. (2025). Artificial Intelligence and Barbarism: A Critique of Digital Reason Athens School, Athens.

Varoufakis, Y. (2024). Technofeudalism What Killed Capitalism. Vintage Books, London.