By Eve Olney. Based in the city of Cork, Ireland, Olney works across multidisciplinary research practice as an independent researcher, activist, creative producer and educator. She is a member of urban activist group Urban React (Greece) and the collaborative commoning project Living Commons (Ireland). Her work is published and exhibited across, art, architectural and sociopolitical activist forums. The following text was written for the anthology «Enlightenment and Ecology: The Legacy of Murray Bookchin in the 21st Century» (edited by Yavor Tarinski, published by Black Rose Books, 2021).

Mapping the Emergence of Non-Disciplinary Practice

This paper outlines how a radical pedagogy[1] of collective design is being developed through a direct democratic common assembly method. This consideration of collective design is driven by a non-expert ethos that enables self-organised, creative initiatives around social living, that work outside of conventional schemes of disciplinary learning and practice. This particular scheme emerged from an idiosyncratic interweaving of different projects and practice research I was involved in from 2014-2017. I began developing a new collaboration of anti-neoliberal praxis, named ArtˑArchitectureˑActivism, in tandem to working with an Athenian-based urban activist group called Urban React in 2017. The collective design scheme is currently being applied within Urban React’s project in the suburb of Kaisariani, Athens, and a project in Ireland called The Living Commons; two very different projects with two very different socio-cultural contexts.

Collective design is critically framed here as both an emergent and continuous material and philosophical process of community building. The underlining organizational principles are drawn from the project of direct democracy as epitomized by Cornelius Castoriadis’s project of autonomy[2] and Murray Bookchin’s conception of communalism through libertarian municipalism.[3] This paper foregrounds how, Bookchin’s work, in particular, critically validates how the project is being developed and its longer-term political ambitions of creating concrete social change in Ireland. A key influence in the formation and development of this process of collective design is Bookchin’s hypothesis on the social ecological reordering of society through libertarian municipalism. The intention is to build upon the philosophical, ethical and material infrastructures of communities through a common assembly process of collective design. These self-governed, commoning communities can then, in the future perhaps, with the support of the broader populace, be regarded as burgeoning municipalities and feasible social alternatives to the current market-driven state policies around housing that is causing a deeper social crisis in Ireland by the day.

The story of this project initially began in Athens in 2017, and the context of this narrative thread – from Athens to Ireland –is central to how each critical reflection and different stages of advancement gradually shape the collective design scheme into a structured socio-political project. I first came across the philosophical and political writings of Bookchin and Castoriadis when commencing research relating to the housing project in Athens. In particular, Bookchin’s critical framing of Communalism, and ‘its concrete political dimension, libertarian municipalism,’[4] seemed to address and bridge the problematic blind spots of patriarchal revolutionary socialism as well as anarchism’s lack of projecting a feasible alternative social imaginary.

My own subject position within this description is relevant in terms of how I amalgamate my accumulated experience as a researcher, precariat, mother, activist and social practitioner to further inform the project. I locate the key point of critically pursuing this endeavour when I left academia in 2017 due to increasing exploitative working conditions within the neoliberal gig economy. As teaching and learning are now economically calculated and seamlessly established within neoliberal Neo-Tech logic[5] it became increasingly difficult to pursue the kind of practice research I am interested in. I have always worked in between disciplines and practices; mainly across cultural studies, social theory, architecture, and art. I also apply an ethnographic approach to my work because engaging with a subject through other people’s experience often challenges the ethnographer to seek alternative faculties of knowing such as embodied, tacit, and sensorial; categories that are often unacknowledged within disciplinary praxis. Validating them as knowledge systems involves not just applying value systems that are human based but also challenges the reasoning behind existing systems of value that are institutionally and economically driven and applied to the general populace in terms of how people are currently valued as ‘citizens.’

Bookchin’s concept of Communalism carries an understanding of equality amongst people in terms of their capacity to be active citizens within the shaping and running of their own communities, through a direct democratic form of organisation. Within this paradigm of governance, individuals are valued on their own human experience and how this helps them address their common needs. He argues that, within a libertarian municipalist economy, for example,

‘we would expect that the special interests that divide people today into workers, professionals, managers, and the like would be melded into a general interest in which people see themselves as citizens guided strictly by the needs of their community and region rather than by personal proclivities and vocational concerns. Here, citizenship would come into its own, and rational as well as ecological interpretations of the public good would supplant class and hierarchical interests.’[6]

Within this pursuit of a ‘public good’ also consists a challenge to existing propagation of human subjectivity. Bookchin’s description of subjectivity moves beyond popular Marxist concepts of citizens as ‘proletariats’ or ‘workers’ in terms of social actors needing to assume the control of production and, in turn, the economy. It also addresses the problematic lack of social duty often embedded within anarchism. Bookchin’s vision of libertarian municipalism, that is channelled through an ongoing collective assembly process, lays the foundations of ‘a moral economy for moral communities,’ where notions of ‘class, gender, ethnic[ity], and status’ are overridden by a shared ‘social interest.’ [7]

I am compelled by Bookchin’s argument, as the shaping of subjectivity through an ideological, social, material process is a preoccupation within my practice research. Dispelling the normalized competitive classification of people within the workforce is entirely conflictual with the current neoliberal subjectivity of competitive entrepreneurship where each citizen allegedly has the ‘freedom’ to create her or his own wealth and well being at an, arguably, unethical competitive cost to others. The concept of ArtˑArchitectureˑActivism, as a scheme of collaborative practice and action, emerged from a strain of research I was conducting in Ireland, regarding the artist’s and the architect’s complicity within oppressive neoliberalist practices and ideologies. The research involved an ethnographic critical approach that considered architecture’s role—as a discipline, practice, and culture—in, what architectural theorist Douglas Spencer refers to as ‘the spatial complement of contemporary processes of neoliberalization.’[8] Architecture’s role in the oppressive shaping of subjectivity became a primary concern within my work. What Bookchin’s hypothesis offers, however, is a more holistic perspective of how citizens can potentially redefine themselves in relation to the kinds of ‘creative and useful work’ that will need doing in order to ‘meet the interests of the community as a whole,’ should they choose to engage with municipal libertarianism.[9] Architectural work will of course be absorbed into this process, as communalism, ‘seeks to integrate the means of production into the existential life of the municipality such that every productive enterprise falls under the purview of the local assembly.’[10] This then progresses the challenge to the neoliberal subject beyond professional practice alone, and situates roles such as ‘architect’ as merely one of many parts of a holistic social process.

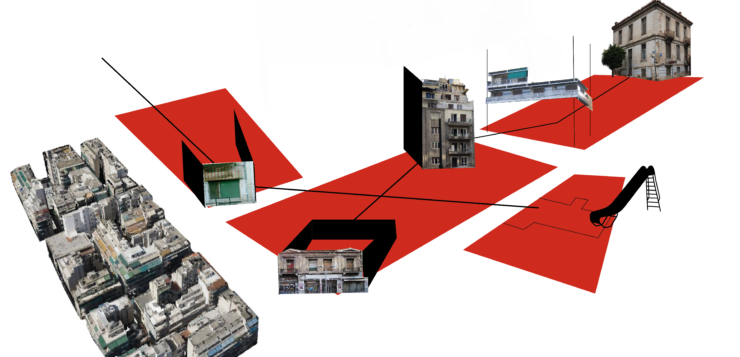

In 2017, ArtˑArchitectureˑActivism was developed in response to addressing how the role of the artist/architect might cultivate alternative, non-hierarchical methods of collaborative practice. It can be understood as a collective curatorial model that employs art, architecture, practice-research and exhibition as an interface for activism, a critique of state institutions, as well as targeting arts funding[11] to initiate long-term social projects challenging precarious social living conditions. This includes moving beyond temporary community-based participatory art engagements and pursuing community building through commoning projects that result in long-term, concrete social change. The project-exhibition scheme is led by activists, artists, architects, and others based across Europe who collaborate with different communities and individuals from the specific city that the scheme is working within at any one time. It engages in the geopolitical and social contexts of the city in a way that directly relates the local to the global. To date, the scheme has produced an exhibition in Athens, named, Inhabiting the Bageion: architecture as critique[12] in October 2017 (and featured Urban React’s Kaisariani housing project), and an exhibition in Cork in September 2019, called Spare Room (Irish Arts Council funded). The latter was themed around the Irish housing crisis and—in keeping with Bookchin’s earlier argument regarding moving beyond generic differences—presented this status of crisis as a commonality across structures of culture, class, ethnicity and personal politics.

Urban React’s Kaisariani Project as a Case Study for Collective Design

Since early 2017, I have been engaged in an ethnographic collaborative practice with Urban React. Urban React is a collective of activists who share a common interest in alternative modes of teaching and practicing architecture as an inclusive collective social practice. We adopt architectural, economic, and socio-political tools to bring people closer to an autonomous and equitable society in the context of common space. Urban React is currently working with the inhabitants of an old refugee housing block in the Athenian district of Kaisariani to renovate their building.[13] Urban React’s goals are to collectively fix the structure of the building, renovate the inhabited apartments, reclaim the central courtyard for the inhabitants’ use and, most importantly, renovate unoccupied apartments for homeless refugee and Greek families. Urban React is introducing a co-ownership scheme to protect the housing block from future gentrification and co-option. Additionally, the inhabitants will have a ground floor apartment for holding collective assembly meetings to manage the day-to-day running of their living environment. This is initiated through an emergent process of collective design and is independently funded.

Early on in the project it was agreed that we should not approach the inhabitants with any kind of political agenda but instead focus on the common problems within the area and explore ways of inclusively working together. There existed the idea of ‘making politics’ as opposed to following any particular political ideology. As people became involved in the collective design process, of improving their own and other’s welfare, a different type of political agency could possibly emerge and be identified within the workings of the group. There is also the understanding that just because there will be space available to hold assembly meetings the people themselves—or maybe few of them—might not avail of the space for this purpose. This is something that cannot be coerced but must emerge within the process of collective design. As Bookchin argues, ‘a Communalist society cannot be legislated into existence’[14] and must happen through a gradual social transformation. ‘What counts is that the doors of the assemblies remain open for all who wish to attend and participate, for therein lies the true democratic nature of neighbourhood assemblies.’[15]

It is through this project that the concept of collective design began to take shape. The initial idea was to develop it outside the limitations of disciplinary architectural practice, but engage with architectural students and individual architects that shared our ethical and ecological concerns. It was understood that collective design needs to be an ongoing, long-term, social project that is never considered to be complete. As previously inferred, its underlining principles were initially drawn from a social condition of direct democracy, characterized by Castoriadis; as a mode of social organisation that is self-instituting and self-limiting. The limitations and shaping of the institutional structures would be determined by immediate needs and actions throughout the process. However, Bookchin’s holistic, social ecological framework of social development as a means of, ‘reorder[ing]social relations so that humanity can live in a protective balance with the natural world,’[16] has facilitated more long-term thinking and planning regarding sustaining the communities that may arise out of this process. This is currently more discernible in the Irish project.

Although we understand collective design to be an emergent, inclusive, collaborative, experimental, social-cultural process it yet needs a definable scheme, both philosophically and practically, without necessarily ‘fixing’ it in a disciplinary manner. The intention is that those who engage with the project will gain experiences and skills where they might be able to identify, in themselves, a more significant social role in the community, through a collective assembly process. Although each collective design project will be different—hence the need for flexibility—‘our basic principles in such cases must always be our guide[17]’. As it is an alternative to conventional architectural practice, its underlining principles must be clear and not become confused with neoliberal practices that claim to be community-centred. Urban sociologist Karol Kurnicki outlines issues with conventional ‘architectural solutions’ as being ‘always provisional and elaborated with unequal share from various social actors and institutions.’ He argues that as the architectural process normally ‘excludes everyone except experts,’ there is a natural ‘elimination of criteria not directly related to architectural discourse and practice,’[18] This excludes and alienates those who do not share the language and specific experience of those leading the project. Architectural theorist, Daisy Froud, highlights a different kind of problem within current community-based projects. She argues that the input from local residents is often overridden by stakeholders who hold professional profiles of expertise. She points out that despite Britain claiming a long social history of ‘community architecture’ implemented within government policy:

“The overall emphasis [in the]most recent government publication on the built environment, 2014’s Farrell Review…seems to be that the purpose of ‘education and outreach’ is to create better informed citizens, who can demand ‘good design,’ as opposed to articulate politicised citizens who might question the social, cultural and economic foundations from which design emerges.”[19]

Her example demonstrates a cyclical transference of opinion regarding what is ‘good’ design and what is ‘right’ for a community that inevitably leads to generic repetitions of what already exists. This contrasts sharply with Urban React’s intended strategy of gaining informed input from communities expressing their specific needs, desires and experiential contexts of their living environment. Our interest in developing a new concept of collective design is in enabling community members recognise their own political agency through determining what kind of community and environment they want to be part of. We recognise this as a mutual learning process that every participant, regardless of their life experience, could undergo.

An expert-led approach is entirely incompatible with this and we therefore understand collective design as new kind of ‘radical pedagogy’[20] that is based upon the premise of equality. It is about the inhabitants of the housing block, as well as the members of Urban React, critically exploring how to be a community and the individual’s role within that process. Scholar of social learning and identity development, Joe Curnow, argues the need for ‘radical theor[ies]of learning’:

“In order to truly theorize an approach to enabling radical praxis, we have to start with an understanding of how people learn… [We need to centre] pedagogical approaches in a theory of learning that explains how people become able to participate well in the work of building radical alternatives.”

Within the concept of collective design, each particular place is an educational space; a site of learning. Therefore, as the core group driving this project, we need to consider what kind of social engagements might lead individuals to re-evaluate their own subject positions for the common good of their community. Curnow argues that ‘more often than not, people become politicized through engagement in communities where particular political analysis and actions are valued and performed collectively.’[21] Bookchin, also projects that, ‘No one who participates in a struggle for social restructuring emerges from that struggle with the prejudices, habits, and sensibilities with which he or she entered it.’[22] It is therefore vital that these collective design projects extend themselves, socially, beyond the actual sites that are being reconfigured, in order to avoid community groups becoming insular or parochial. In 2016, the Kaisariani Summer School was organised between Bern School of Architecture and members of Urban React. Architectural students spent a few weeks making studies of the housing block and talking to the inhabitants by way of engaging them in imagining future designs for the courtyard as a commoning space. This opens up the student’s experience to a new field of social practice. The main intention of the exercise lies in attempting to shift people’s perspective as they witness the gradual improvement of their living environment. Therefore a ‘subjective and material transformation’ occurs simultaneously, through the collective design process. Educational theorist, Etienne Wenger discusses how the social and material work together:

“Engagement in social contexts involves a dual process of meaning making. On the one hand, we engage directly in activities, conversations, reflections, and other forms of personal participation in social life. On the other hand, we produce physical and conceptual artifacts—words, tools, concepts, methods…and other forms of reification—that reflect our shared experience and around which we organize our participation.”[23]

Geographer Melissa García-Lamarca argues that a vital component of the process is that the inhabitants arrive at a point where they begin to ‘[generate]their own learned political practices’ and control and direct ‘the way knowledge is created and transmitted for [their own]community development.’[24] It must be the people themselves that lead decision-making and implement the changes on their own terms. Bookchin points to the transformative effects that ‘deal[ing]with community affairs on a fact-to-face basis,’ can have on those participating in ‘popular assemblies.’ Citizens become familiar with ‘making policy decisions in a direct democracy and giving reality to the ideal of a humanistic, rational society’[25] on their own terms.

Critical Reflections on the Development of Collective Design

Working within a people-led framework of collective design has proven difficult in the Kaisariani project due to social issues that are historically and culturally ingrained within this fractured community. Building up an inclusive set of relations with the inhabitants is a challenging and slow process. In 2017 Urban React used a converted van parked in the courtyard of the housing block, as an information centre to encourage participation in the project. This created visibility for the project and opportunities to build up trust and knowledge of each other. Although laborious and time-consuming this proved to be beneficial and a significant number of people signed up for the project. However, this kind of continuous engagement is not sustainable due to the personal situations of Urban React and, since then, contact remains quite sporadic. Some inhabitants have been interviewed on video for an ethnographic arts project as part of Art Architecture Activism. Recent contact with the residents has included filming an on-site video clip for an upcoming Fund It scheme.

Urban React also held communal eating events and social get-togethers in the courtyard to inspire a different perception of it as a social space. The Kaisariani Summer School architectural posters were used at commoning events to demonstrate future possibilities of the space. García-Lamarca discusses the creation of political subjects through collective knowledge and action. For example, during the communal eating event, people who had never met could identify themselves as being part of a group of neighbours. García-Lamarca stresses the importance of this concrete realisation ‘that you are not alone,’ Seeking solutions to everyday, practical issues through collective design can enable a process of re-evaluation that directly challenges everyday attitudes of disinterest, apathy, disillusionment, and, ‘people [can]become re-energized and injected with hope, and move through a process of re-belonging.”[26] Bookchin further argues that, within this ongoing shift of perspective, ‘Hopefully, such prejudices, like parochialism, will increasingly be replaced by a generous sense of cooperation and a caring sense of interdependence.’[27] Arguably, this aligns with Wenger’s view that a ‘community of practice’ can be considered ‘as a social learning system.’ According to Wenger a community of practice occurs when a group of people collectively accumulate knowledge and practices and ‘become informally bound by the value they find in learning together.’[28] Curnow applies Wenger’s theory to social movements and the kind of ‘tacit learning [that occurs]rather than explicit training on the ground.’[29] Within collective design, ‘the community itself is the curriculum [as]members are learning, reproducing, and innovating through their work together.’[30]

However, people-led collective design is always shaped through the specific social context and it takes time and consistency to build up trust and a shared sense of community. Following a number of instances where some inhabitants displayed racist attitudes towards others at social gatherings, it was understood that there needs to be a more informed and structured approach towards dealing with conflict. For example, as opposed to responding to conflictual situations as they occur, it was agreed that there should be an inbuilt systemic way of dealing with contestation within the collective design process. However, due to the ongoing difficulties and delays experienced by Urban React, collective design as a concept has largely remained analytical up until now. When discussing the pursuit of libertarian municipality, Bookchin points out that it ‘must be conceived as a process, a patient practice that will have only limited success at [times], and even then only in select areas that can at best provide examples of the possibilities it could hold if and when adopted on large a scale.’[31] Urban React is committed to continuing this project despite the obstacles. Recent meetings with the inhabitants have needed to be either one on one or more loosely generated but there are plans to begin to formulate more structured gatherings according to the principles of collective design, before any construction begins.

The Living Commons – an Irish Context

It was during this experience with Urban React that I also began collaborating with individuals in Ireland who were interested in the idea of community building through a people-led collective design process. In response to the ongoing precarity in Ireland that we and others (in worse situations) are living within, we began developing the idea of creating a holistic, social ecological, commoning living, and working environment in Ireland—called the Living Commons—as an alternative living model to what is being churned out by the Irish government in response to the housing crisis.[32] The Living Commons is implemented through collectively-led, social ecological cultural programmes that enable those in precarious living situations equal participation in social, cultural, economic, and political life through the initiation of autonomously-run collective design programmes. Similar to the Urban React model, the Living Commons is researched and developed through cultural co-operative programmes channelled through a common assembly mode of governance. The objective of building a direct democratic living and working environment draws significantly from Bookchin’s emphasis on the question of power within the idea of libertarian municipalism. He talks about ‘the tangible power embodied in organized forms of freedom that are rationally conceived and democratically constituted.’[33] When partaking in public discussions around current sets of conditions in Ireland, I have noticed a tendency to categorise the social into different kinds of crisis. People talk about the banking crisis, and the housing crisis, or the crisis in healthcare as an attempt at coordinating a counter argument amidst a collective sense of powerlessness. People situate individual problems within a global scale of crisis that they believe they have no control over.

As in the rest of Europe, a crisis in governance has drastically reduced the standard of living in Ireland, in the last decade, while the price of properties and rental accommodation continues to soar. The number of homeless families has increased by 348% since 2014. There are currently over 10,400 homeless adults and almost 4,000 children in emergency accommodation (in a population of 4.88 million). Yet, the idea of cohousing, much less commoning living, is quite an alien concept in Ireland. This can be attributed to the absence of legal structures that can accommodate this scheme of living in tandem with the Irish Central Bank’s prevention of community banks and cohousing Trusts to operate in Ireland. Home ownership is historically ingrained into Irish culture and until recently renting was only seen as a stepping stone to owning your own home. Despite the same two parties (Fine Gael and Fine Fail) historically leading the populace into further crisis people yet look to the state for solutions. Bookchin argues that this can also be regarded as an opportunity for activists who are attempting to implement radical difference. He believes that people in crisis, ‘can be mobilized to support our anarchist communist ideals because they feel their power to control their own lives is diminishing in the face of centralized state and corporate power.’[34] García-Lamarca further contends that, ‘Collective advising assemblies are spaces where people…begin to disidentify with their position in the dominant economic and political configuration and begin to shed their guilt, shame and fear… and materialize new ways of acting and being.’ [35]

There is currently a promising attempt to bring cohousing into Ireland, led by SOA[36] (Self Organised Architecture). The emerging models within this, work within a capitalist system and are dependent upon initial economic investment to set up a cohousing system. Alternatively, the Living Commons has a specific focus on those who are currently living precariously, including homeless, people in emergency accommodation, direct provision[37] and/or in an insecure rental situation. The objective is to begin with a systemic structure that can coordinate social projects as self-governed political projects. Non-expert does not assume that participants have equal knowledge as people have variable social advantages and disadvantages. A people-led process does assume an equal capacity to contribute and learn and become an active, self-empowered member of a community. A number of social enterprises will be initiated by engaging with existing projects, in perma-farming, people’s kitchen and bakery, near zero energy initiatives, food and craft markets. We are working towards a self-sustainable living model within three to five years.

Reflecting upon the logistics of the Urban React project, we concluded that the Living Commons requires full-time active members that can steer the project through the process of collective design towards a more holistic political project of direct democracy. A marked difference to the Kaisariani project is that we are initiating a commoning community as part of the collective design process, whereas at Urban React, are working with an existing (and segregated) group of inhabitants. Unlike Greece, we have the advantage in Ireland of an arts council funding stream that grants sufficient autonomy to the projects and artists it funds. We secured arts funding in 2018-2019 through the Art Architecture Activism scheme with a proposal of producing long-term projects that addressed the Irish housing crisis. The projects—that included the Living Commons—were given a public platform through an exhibition, titled, Spare Room,[38] in Cork city, September 2019. Spare Room became a vehicle from which to begin mapping and engaging with existing social projects in Ireland, and beyond, that (whether subconsciously or deliberately) work on principles of commoning and/or self-organisation in Ireland. Over the two weeks of the exhibition we held twenty-three workshops and discussions of commoning practices around eating, making, seed banking, self-building, printing, reinstituting, mapping networks of existing commons and digital commoning. Additionally, we began an ongoing collaboration with art and sustainability practitioner, Spyros Tsiknas[39] and are integrating his practice research on ‘role play for non violent action’ within our concept of collective design. Spare Room also functioned as an inclusive social space and we connected with numerous schemes and organisations who are interested in becoming involved in the Living Commons. Finally, through this initiative we have also secured an autonomous space with some land to begin the entire process.

Conclusion: The Next Steps

The next steps include creating a visible online mapping of projects and individuals that are already involved in self-organisation in Ireland and begin interconnecting these groups through collective design programmes in the Spare Room space. As each programme develops—whether it is the people’s kitchen, perma-farming, non violent action, self-building, or others—they are interlinked with other programmes both within Spare Room and other locales. For example, the farming is interlinked with the people’s kitchen and approaches to dealing with mental health which is itself interlinked with other programmes and so on. The objective is to build up a broad networked social framework where people are democratically responding to their own and others’ needs. The existing programmes have been set up by those who have specific needs and have acted upon those needs; ‘a communal society orientated toward meeting human needs, responding to ecological imperatives, and developing a new ethics based on sharing and cooperation.’[40] In Ireland the biggest challenge to creating an alternative social imaginary is the neoliberal normalization of crisis and poverty and the dominant national narrative that we are all complicit within our own crisis. There is widespread apathy, as well as the aforementioned reliance on party politics to resolve people’s problems. This aligns with Bookchin’s argument that, ‘The State justifies its existence in great part not only on the indifference of its constituents to public affairs but also—and significantly—on the alleged inability of its constituents to manage public affairs.’[41] Working through a radically different system of human-led values and needs can create an inclusive educational space of political and social praxis.

As aforementioned, an acknowledgement of different modes of ‘knowing’ can contribute to shifting normalized assumptions about seemingly concrete sets of socio-political conditions. For example, there is currently no value given to the kind of knowledge that comes from the experience of surviving poverty. Cultures of resistance must begin with a shared value system that is informed by people’s needs and not economics. As Irit Rogoff argues, this entails placing value on:

‘Knowledge that would […] be presented in relation to an urgent issue, and not an issue as defined by knowledge conventions, but by the pressures and struggles of contemporaneity …in the sense that ambition knows and curiosity knows and poverty knows.”[42]

It is by working across different ‘faculties of knowing’ that collective design functions as an emergent ‘social theory of learning.’ It opens up a critical space where people can situate their own subject position in terms of how to be part of a sustainable and equal community. Within the praxis of learning through collective design the philosophical is always integrated within the doing/practice. This rejects the notion of a separation between intellectual knowing and embodied knowing. Such a social nexus of community learning and doing can build a culture of resistance counter to the current oppressive dominant order. As Bookchin argues,

“The citizens must be capable intellectually as well as physically of performing all the necessary functions in their community that today are undertaken by the State… …Once citizens are capable of self-management, however, the State can be liquidated both institutionally and subjectively, replaced by free and educated citizens in popular assemblies.”[43]

[1] The term ‘radical’ is in reference to creating alternative teaching and learning methods that can rupture the current conventional ‘fixed’ disciplinary methods.The Radicalization of Pedagogy: Anarchism, Geography, and the Spirit of Revolt. (Ed.s) Simon Springer, Marcelo Lopes de Souza, and Richard J. White, Rowman & Littlefield (London: New York, 2016).

[2] Cornelius Castoriadis. The Imaginary Institution of Society. (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005).

[3] Murray Bookchin. The Murray Bookchin Reader, ed. Janet Biehl. (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1999).

[4]Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), p.xvii.

[5] In his paper, ‘The Neoliberal Academy of the Anthropocene and the Retaliation of the Lazy Academic’, Ryan Evely Gildersleeve uses the term “Neo-Tech” to describe the ‘the faculty performance review system’ that channels, ‘the reconfiguration of knowledge through neoliberalism’s biopolitical technologies’,’to quantify [his]scholarly contributions from the previous year’. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, DOI: 10.1177/1532708616669522. Downloaded from csc.sagepub.com at University College Cork on November 27, 2016

[6] Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), p91.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Spencer Douglas. The Architecture of Neoliberalism, (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), pp. 1-2.

[9] Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), p19.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Within an Irish context, despite the arts council being publicly funded it is perhaps the last sphere in public life that offers autonomy to those who secure funding.

[12] https://www.facebook.com/inhabitingthebageion.

[13] https://urbanreact.wordpress.com/ https://www.spareroomproject.ie/urban-react

[14] Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), p29.

[15] Ibid, pp.53-54.

[16] Ibid, p.14.

[17] Ibid, pp.60-61.

[18] Karol Kurnicki. ‘Towards a spatial critique of ideology: architecture as a test’, Journal of Architecture and Urbanism, 38:1, (2014), pp80-89, DOI: 10.3846/20297955.2014.893642, 2014. P86. (Accessed 08 September 2016).

[19] D. Froud. ’Normal People’ and the Politics of Urban Space, in Froud and Harriss (ed.s) Radical Pedagogies: Architectural Education and the British Tradition, RIBA Publishing, (2015), p51.

[20] See endnote No. 1.

[21] J. Curnow, ‘Towards a Radical Theory of Learning: Prefiguration as Legitimate Peripheral Participation,’ In (ed.s) Springer, Lopes de Souza and J. White, The Radicalization of Pedagogy: Anarchism, Geography and the Spirit of Revolt, (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), p27.

[22] Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), pp89-90.

[23] Etienne Wenger. Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: The Career of a Concept, 10.1007/978-1-84996-133-2_11, (2010). https://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/09-10-27-CoPs-and-systems-v2.01.pdf (Accessed 12 September 2018).

[24] M. García-Lamarca, ‘Creating Political Subjects: collective knowledge and action to enact housing rights in Spain,’ In Community Development Journal, Vol 52 No 3 July 2017, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p433.

[25] Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), pp17-18.

[26] M. García-Lamarca, ‘Creating Political Subjects: collective knowledge and action to enact housing rights in Spain,’ In Community Development Journal, Vol 52 No 3 July 2017, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p427.

[27] Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), pp89-90.

[28] E. Wenger, R. McDermott, W. Snyder, A guide to managing knowledge: Cultivating Communities of Practice, (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press, 2002), p4.

[29] J. Curnow, ‘Towards a Radical Theory of Learning: Prefiguration as Legitimate Peripheral Participation,’ In (ed.s) Springer, Lopes de Souza and J. White, The Radicalization of Pedagogy: Anarchism, Geography and the Spirit of Revolt, (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), p32.

[30] Wenger (1998) cited in Curnow (2016) p33.

[31] Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), p60.

[32] Irish housing minister Eoghan Murphy, received public backlash this year when he announced the development of a new co-living model where dozens of people would be required to share a kitchen. He likened it to living in a ‘boutique hotel’.

[33] Murray Bookchin. ‘Thoughts on Libertarian Municipalism’, This article was presented as the keynote speech to the conference “The Politics of Social Ecology: Libertarian Municipalism” held in Plainfield, Vermont, U.S.A., on August 26-29, 1999. The speech has been revised for publication. This article originally appeared in Left Green Perspectives (Number 41, January 2000). http://social-ecology.org/wp/1999/08/thoughts-on-libertarian-municipalism/

[34] Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), p56.

[35] M. García-Lamarca, ‘Creating Political Subjects: collective knowledge and action to enact housing rights in Spain,’ In Community Development Journal, Vol 52 No 3 July 2017, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), p421.

[36] https://soa.ie/

[37] Direct Provision is the Irish government’s accommodation scheme for people seeking asylum. There is widespread condemnation and activism regarding having these for-profit centres shut down due to the inhumane conditions that people are forced to live under. See, https://www.masi.ie/

[38] SPARE ROOM is both the title of the exhibition co-produced by myself and artist/publisher Kate O’Shea as well as the ongoing programme that the Living Commons is being developed within.

[39] https://spytsiknas.wixsite.com/sustainable-art/blog—projects/author/Spyros-Tsiknas

[40] Murray Bookchin. The Next Revolution, Popular Assemblies and the promise of Direct Democracy. (London: Verso, 2015), p85.

[41] Murray Bookchin. The Murray Bookchin Reader, ed. Janet Biehl. (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1999), p3.

[42] I. Rogoff. ‘Free’, e-flux journal #14 March 2010, p10. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/14/61311/free/

[43] Murray Bookchin. The Murray Bookchin Reader, ed. Janet Biehl. (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1999), p3.